By W. Brent Seales, professor and chair of the Department of Computer Science at the University of Kentucky

Fabrizio Diozzi, director of the Officina dei Papyri at the Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, walked me to the balcony where we could see the Tyrrhenian Sea stretching from the library in Naples toward Capri and beyond. We were getting to know each other, admiring the beauty of the Bay of Naples and talking about music. He had a passion for the American music recording industry, and his wide-ranging interests and knowledge inspired me.

“Muscle Shoals,” he chanted as he turned to me with a smile.

The name of the tiny, nondescript river town in rural north Alabama was not what I expected to hear from the Neapolitan conservator who was overseer of the world-famous papyri from Herculaneum. But during the middle decades of the 20 th century, two small recording studios in Muscle Shoals had produced amazing results, turning the town into a legendary session retreat. Artists from all over the world sought the unique R&B funk of the “Muscle Shoals sound.” Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, The Rolling Stones and many others achieved their dreams with help from the excellent, innovative and talented Muscle Shoals team.

Excellence attracts dreamers, who are shaped by their tenacious pursuit of dreams into talented achievers. Having risen to the pinnacle of his profession, Fabrizio recognizes excellence and understands its power. The potential of our own joint pursuits brought to his mind the story and symbol of Muscle Shoals.

This conversation with Fabrizio really moved me, because the fact is, excellence is hard to achieve, and no one has exclusive rights to it. Collaborative research programs like ours must fight their way to excellence in their own way and time. We are fortunate to have a clear pathway to research excellence at the University of Kentucky thanks to our talented students, enterprising faculty members and support from colleges like Engineering, where we have strong entrepreneurial values, visionary leadership and accomplished, dedicated alumni willing to invest in our future success.

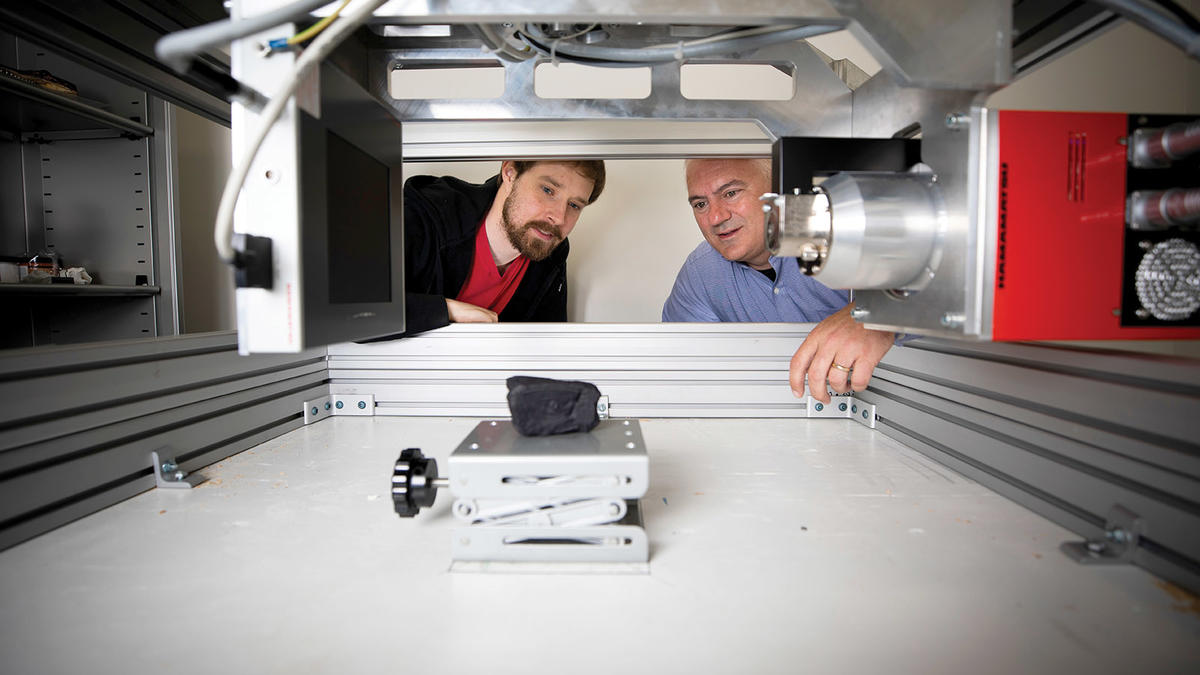

My research program, called the Digital Restoration Initiative (DRI), is focused on engineered systems and software (imaging systems, software algorithms, data science) that are designed to realize the dream of reading the invisible library. The invisible library is the plethora of existing written material—manuscripts, scrolls, fragments—too badly damaged to open physically. Surprisingly, a wealth of material like this resides in museums and libraries around the world. It is at once mysterious, rare and ugly. Things that are too damaged to read or even to be handled safely are not usually considered beautiful, but I have come to see these objects through different eyes, those of the problem-solving engineer. I imagine the future beauty that will emerge with the rescue of their unique and ephemeral narratives.

This dream includes Fabrizio’s scrolls from Herculaneum. The first one I saw in person was in 2005 in Naples. Even then, as a newcomer to the world of classical antiquities, I understood the elusive, enigmatic nature of the scrolls. Rescued 250 years ago from the remnants of the legendary A.D. 79 explosion of Mount Vesuvius, the scrolls have undergone painstaking study by renowned scholars from around the world and were even immortalized in poetry by none other than William Wordsworth. Later that summer at Oxford University, I presented my own idea about the scrolls—a specific technical plan for how I thought one could be virtually opened and read. This material is the stuff of dreams.

My collaboration with the talented Fabrizio is remarkable for its rapid coalescence, and it has been accelerated by the convergence of three crucial elements in my research program at the University of Kentucky. This coming year stands to be one of the most exciting I have ever known.

The first and central element, which is beloved by those of us who are engineers and computer scientists, is the technical approach. After pushing for more than five years against seemingly insurmountable limits in imaging technology and data science, we broke through last year with an artificial-intelligence-based approach to “virtual unwrapping.” We already have a working software pipeline that provides a pathway to recover and redeem writing from damaged material when the ink responds well in X-ray tomography. But this year we were the first to show that the special, elusive ink from Herculaneum (carbon “lamp” black that effectively “hides” in tomography) and materials that have similar composition can also be seen and read from documents without first opening them. We use a machine-learning approach, creating a large-scale neural network that can recognize and enhance the ink even while evidence of that same ink cannot be seen with the naked eye. We published our approach earlier in the year. Similar methods are also being developed for clinical applications in order to flag health concerns well before they are even visible to the trained eye of a radiologist.

The second key element is funding. Bridging our way and cheering us onward to external research support is the generosity of UK Alumni and supporters John and Shirley Kyle, John and Karen Maxwell, Craig Adams, and Lee and Stacy Marksbury. Premised on the successful completion of three major NSF awards over the past two decades, this year we received support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Humanities Research Council of Great Britain.

Finally, with Fabrizio’s help and support, the DRI through the University of Kentucky has signed a digital rights agreement with the Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli. This agreement gives me the opportunity to digitize the entire Hercualeum papyrus collection and release all the results as open scholarship. The collection represents 1,800 scrolls found at Herculaneum: 6,000 trays of opened scrolls with visible text that is very difficult to see and almost 900 intact scrolls and scroll chunks. Only 17 scrolls from Herculaneum are not in the collection in Naples, and we now have access to those as well.

Our goal? To produce the best digital images of the already opened scrolls that the world has ever seen, and to read the ones that have never been opened…without the need to open them.

The Neapolitan papyrus conservator and I are not so different. We love challenges and we are inspired by excellence. Together we are approaching the Herculaneum papyrus collection in Naples, hoping to change the world of papyrology and the classics forever by moving the Herculaneum scrolls from the invisible library into the visible, digital one.

And Muscle Shoals is such an apt image. The Alabama studio that hosted musicians from all over the world and inspired them to do their best work is exactly what I hope to build at the University of Kentucky. Well, not a music studio, but the DRI Lab. Centered in the UK Department of Computer Science, and in partnership with the best collections worldwide, the DRI could become the premier place for damaged manuscripts to come for restoration, analysis and new discoveries—a magical retreat for the repair and restoration of seemingly lost manuscripts if you will.

While we currently lack the equipment and sustained funding for the laboratory I envision building here at UK, we hold something very powerful: collaborators like Fabrizio; the courage to explore and discover; and the dream to drive us onward.

As happened with Muscle Shoals, sustained excellence will soon have people asking not how this could be possible at the University of Kentucky, but what will be our next dream?

O ye, who patiently explore

The wreck of Herculanean lore,

What rapture! could ye seize

Some Theban fragment, or unroll

One precious, tender-hearted, scroll

Of pure Simonides.

That were, indeed, a genuine birth

Of poesy; a bursting forth

Of genius from the dust:

What Horace gloried to behold,

What Maro loved, shall we enfold?

Can haughty Time be just!

- William Wordsworth, "September, 1819"