By Lindsey Piercy, UKPR

Barry Allen, of Nashville, Tennessee, describes his family as tight-knit. Together, he and his twin brother, Scott Allen, and their sister, Roberta Callahan, keep the memory of their late mother and father alive but since their passing, a mystery of sorts has confounded the siblings. Who knew a professor at the University of Kentucky held the key to unlocking that mystery?

Barry remembers his father, Eddy Allen, as exceptionally smart and extremely sociable.

In the 1960s, the family was living in Atlanta. Eddy was selling high-grade steel used in sophisticated metal working/tooling operations. He also sold a liquid coolant to help remove heat from those operations and protect the tools, but he realized the coolant wasn't consistently reliable. Starting in October 1967, Eddy decided to create a better, and ultimately more dependable, coolant. This was no simple feat. Barry recalls his father spending countless hours studying and collaborating, often in their kitchen.

"Dad always reminded us to 'think positively.' He felt that any roadblock could be overcome by believing 'I can do it.' I think this philosophy made it possible for him to invent a series of chemical formulas, without having any training or background in chemistry," Barry said.

In December 1967, the salesman turned inventor produced what he deemed a successful solution. As a result of countless experiments, Eddy created a synthetic cutting compound-coolant for machining purposes. He called it "Micron 10-5." Eddy eventually designed a small chemical plant to manufacture the coolant, which became operational in March 1969.

Scott recorded his father's complex work in a simple notebook, and those notes were later photocopied. The goal was to preserve the potentially groundbreaking formulas, but triumph was followed by tragedy. Eddy was diagnosed with esophageal cancer on his 52nd birthday in 1978. He was given three to six months to live but died only six weeks later.

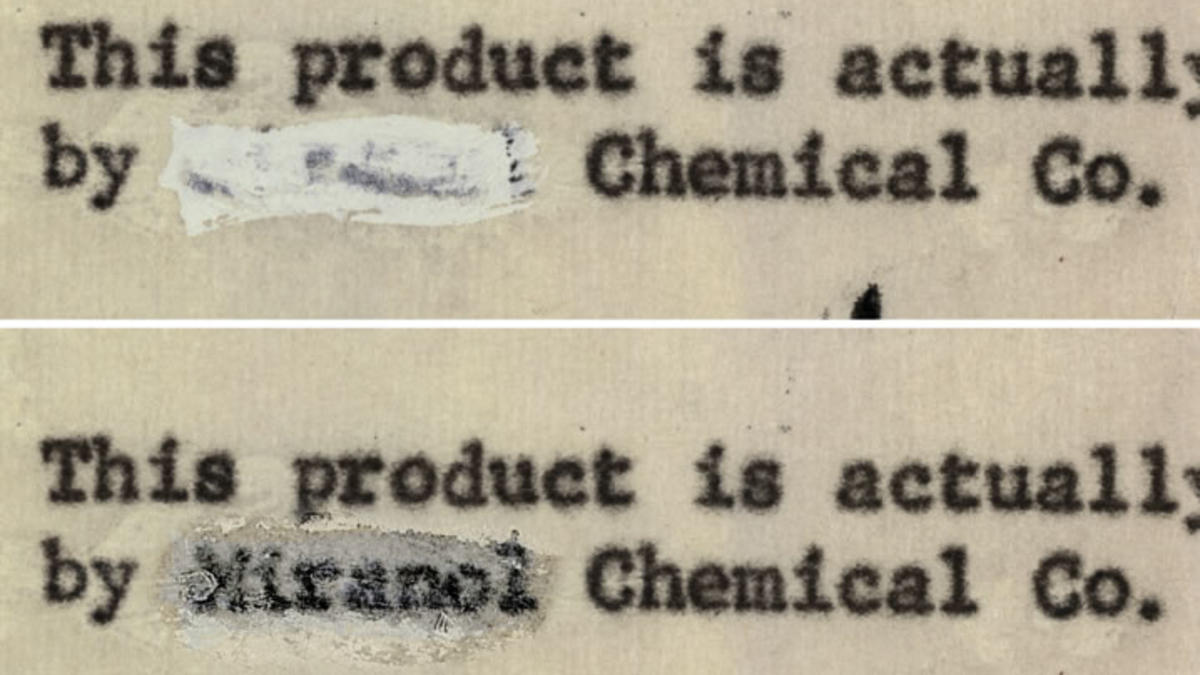

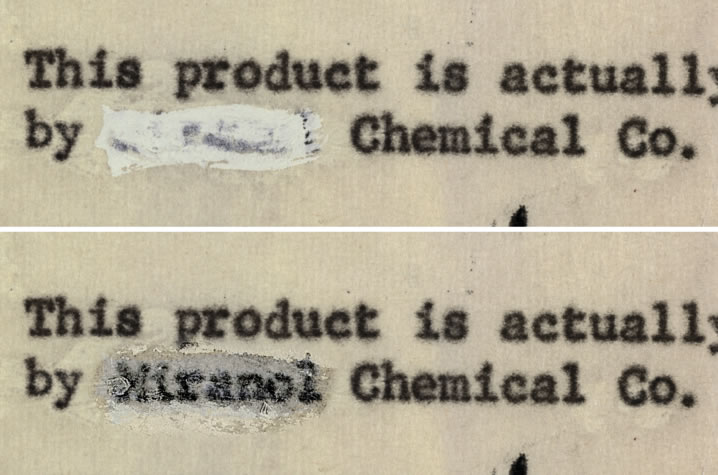

For reasons the siblings never completely understood, their mother, Sylvia, used liquid correction fluid to cover critical parts of the formulas. With the stroke of a Wite-Out brush, Eddy's work had been seemingly erased. Barry believes his mother's intentions were to protect the proprietary nature of the formulas. A decades-long quest for answers thus ensued.

"Over the years, I remained on the watch for some solution to our family's mystery," Barry said. "I had hope, but my siblings and I all had our regular lives to live, and finding the solution just took a back seat."

Following his mom's death in 1998, Barry continued to search for ways to make the invisible visible again. He even reached out to the manufacturer of Wite-Out, to no avail. Optimism was starting to fade.

Until Easter Sunday, 2018.

That evening, Professor Brent Seales, chair of the College of Engineering's Department of Computer Science, was featured on an episode of the long-running CBS show "60 Minutes." Barry watched closely and listened carefully as Seales detailed his unprecedented efforts to digitally unroll ancient scrolls.

In 2016, Seales developed the "Volume Cartographer," a computer program for locating and mapping 2D surfaces within a 3D object. Using the tool to reveal sealed secrets has become his area of expertise.

After the episode, Barry recalls feeling a sense of renewed hope. He reached out to Seales through email — the subject line read, "Request for Assistance — Deciphering a Family Owned, Secret Chemical Formula."

"To say I was elated that Professor Seales was interested in my family's project is an understatement. I did a lot of smiling," Barry continued. "I kept visualizing the burned-to-a-crisp cylinder that had been shown on TV and thinking, 'our problem just has to be easier to solve.'"

Christy Chapman, research and partnership specialist, responded on behalf of the team to Barry's plea for help. Like everyone on Seales' staff, she is a firm believer in not conducting research purely for research's sake.

"The Digital Restoration Initiative (DRI) is not just about advancing our scientific agenda; we also want to see successful application of the tools we create so that knowledge advances in all areas, whether that be history, literature, biblical studies or even in a family’s legacy, like that of the Allens."

"We are a public university and that means when people reach out to engage, our first response should always be to try to help," Seales added. "That often has direct impact for Kentuckians but can also have broader impact when we demonstrate the good things going on here to a national and even international audience. And in the end, the results can be incredibly personal."

For Barry and his family, it was personal. On April 16, with original documents in hand, he drove to Lexington to personally deliver them to Seth Parker, the DRI technical director. Barry hoped the end to a 40-year-long mystery was in sight, but for Seales, and his dedicated staff, the real work was just beginning.

"UK staff are crucial to my effort in building the DRI. Once collaborative partnerships are established, experienced staff are central to the execution of the work, bringing a high level of professionalism and experience to lead the way for our students, who learn from their example," Seales explained. "And of course, the lab instrumentation and data science skills we need, such as the capture and processing of tomography and multispectral photography, are tremendously important in reaching the ultimate aim of reading and restoring ancient texts."

Over the next month, Parker worked to uncover the formula using a multispectral imaging system, which takes high resolution photographs while the pages are exposed to various wavelengths of light. There was no guarantee of success, but the team remained optimistic.

"Everyone on this team has high standards for excellence, and the results we achieve attest to that," Chapman continued. "A lot of people think we just push a button, and out pops a beautifully rendered page, but nothing could be farther from the truth. Restoring these damaged texts requires a lot of painstaking work in the computer lab."

The painstaking hours would pay off. In May, Barry received a message from Seales that read, "the results are stunning." Two weeks later, he returned to the Commonwealth for the long-awaited reveal.

Barry couldn't help but smile as a short video began to play. Before his eyes, the formulas became visible, and just like that, the mystery vanished.

"Seeing my dad's handwriting appear made me feel proud to know that all his hard work was no longer lost and unavailable to our family. I had the very real sense that my dad was smiling down on that room," Barry said.

While age-old questions have been answered with modern day technology, it's uncertain how and where Eddy's product will be marketed in the years to come, but Barry continues to channel his father's unfailing optimism and "think positively."

"I will tell anyone and everyone who is willing to listen that the Digital Restoration Initiative has an astonishing, mind-blowing capability that can change previously unusable documents into real-world, usable texts. The possibilities for academic and commercial usage seem endless."

This article originally appeared in the August 16, 2018 edition of UKNow. To see the original article, click here.